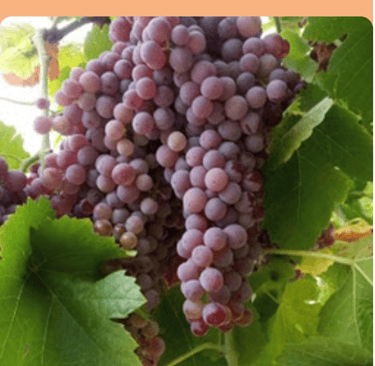

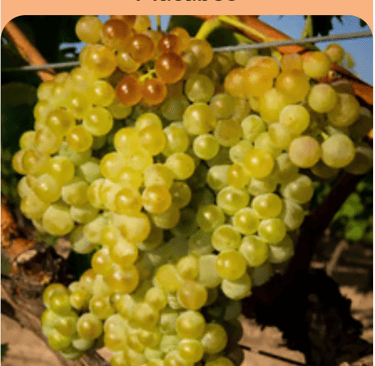

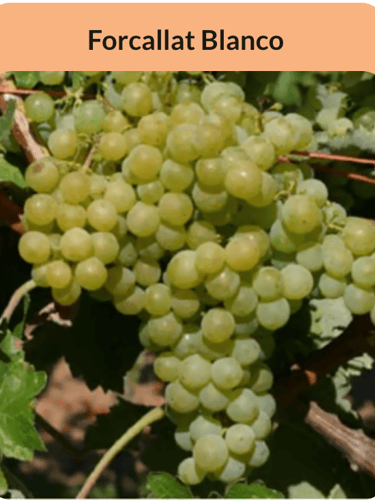

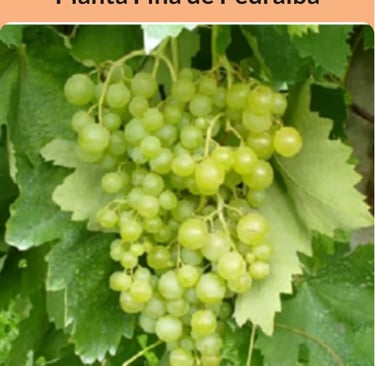

Varieties of grapes

The varieties you'll find here aren't found in every vineyard. Some were on the verge of disappearing completely. Others survived for decades in forgotten terraces, preserved by winegrowers who simply didn't uproot them when asked to do so.

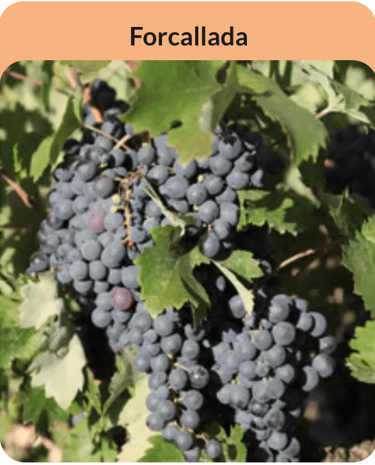

Between 1975 and 2005, 60,000 hectares of vineyards were uprooted in Spain. Here in Valencia, we lost Planta Nueva, Forcallada, Mandó, and Bonicaire in quantities that seemed irreversible. But some vines endured. Not because they were valuable on the market. Because someone decided to preserve them.

Today, these varieties are being vinified again. Not because they're fashionable. Because they are irreplaceable genetic material. An old clone of Bobal, a 100-year-old Merseguera, a Bonicaire that barely remained in three plots: each of these varieties has centuries of adaptation to this specific territory—to its climate, its soil, its conditions. You can't replicate them. You can only preserve them or lose them.

The producers who work with these grape varieties are vineyard archaeologists. They recover what others have uprooted. They vinify varieties without a conventional market. They maintain old vines when replanting would be more profitable.

Here we document each one: its history, its behaviour in the vineyard, its sensory profile, and the winemakers who are committed to it today.

Click on any variety to explore its complete information and discover which wines are available.

Por qué estas variedades

A modern Bobal and an old Bobal clone are not the same plant. The old clone produces less volume but more complex tannins. The old Merseguera has a more vibrant acidity. The old Monastrell responds differently to drought than the productive Monastrell of the 20th century.

These differences are not romantic. They are genetic.

Each of these varieties was naturally selected over centuries. Generations of winemakers observed which vines withstood drought, which ripened well in a specific climate, and which wines were balanced. Not with science, but with experience. This is natural selection applied to agriculture.

The result: nothing adapted to this soil, this climate, these conditions. A Verdil from Alto Turia is different from a Verdil from another region because for 200 years only the plants that understood that specific terroir survived. This cannot be replicated.

But here's the catch: these old clones don't work with industrial winemaking. They don't respond well to technical adjustments. They require minimal intervention, spontaneous fermentations with native yeasts, and trust in the process. That's why they almost disappeared in the 20th century, when the industry demanded volume and predictability.

Now that the market is rediscovering diverse wines, and science recognises that biodiversity is a defence against climate change, these varieties—which we almost lost—turn out to be exactly what we need. They have centuries of adaptation to drought, pests, and climate variability. Nothing that the modern market discarded, but which the climate crisis is demanding.

Recovering them is not nostalgia. It's genetic preservation. It's acknowledging that our grandparents knew something about how to live in this land that the industry has forgotten.

The varieties in this section are not relics. They are living tools for making wine adapted to the future.